In all the Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystems-Climate Nexus systems analysed by the Horizon 2020 REXUS project, agriculture plays a key role. Understanding the energy requirements of agriculture in particular is key for long-term planning for climate change mitigation and resilience. REXUS partner Circe has developed a methodology to assess the energy needs and greenhouse gas emissions for different crops in the REXUS pilots, providing data that policymakers can use to effectively align agricultural and energy policies, such as promoting smart use of fertilisers, energy-efficient irrigation systems, encouraging renewable energy use in agriculture, and supporting less intensive farming practices through appropriate incentives.

GWP-Med, Rexus Communication & Dissemination leader, interviewed Andrea Carrascosa Flores (left) and Carlota García Diaz (right), Technical Researchers with Circe.

Q. Can you briefly explain what is ‘carbon footprint’ and ‘carbon accounting’?

A. In the context of the REXUS project, carbon accounting is the process which measures and tracks the total emissions generated throughout the life cycle of a certain amount of crops, produced in a certain time period[1].

The carbon footprint, on the other hand, shows the total emissions per unit of crop. In the context of REXUS, this indicator is defined as “a unified measure of the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions generated in the life cycle of one kilogram of crop”[2], expressed in CO2 equivalents per kilogram of crop. While some methods tend to oversimplify, we have chosen the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) method as a useful tool which presents a system-level perspective, integrating environmental impacts resulting not only from carbon dioxide emissions, but also from other greenhouse gas missions such as nitrous oxides and sulphur dioxide.

Q. How are you developing and applying this methodology in the REXUS project?

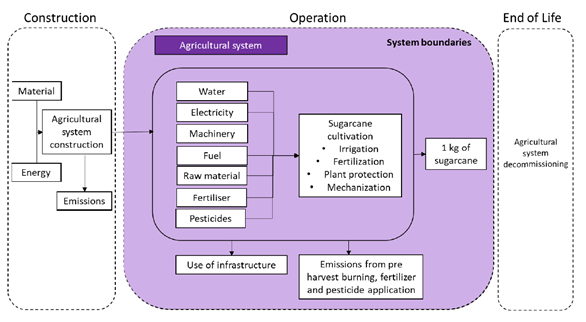

A. LCA is a standardized methodology which assesses potential environmental impacts along the life cycle of a product (in this case, a crop such as sugarcane), starting with the extraction and processing of the raw materials, manufacturing, operation phase and end-of-life. The following diagram shows the different boundaries considered for the crops in this analysis, giving the example of sugarcane; all material and energy considered from the construction of the agricultural system, passing through its use phase and ending with the cultivation of the crop.

In this way, we are able to identify “hotpots” in the agricultural system in terms of the impacts of carbon and energy emissions produced due to the use of fertilizers, pesticides, machinery, irrigation and other inputs that comprise the operation phase of crop production.

Q. Did you find important differences in carbon footprint between crops?

A. The LCA methodology was applied to the Júcar River Basin District, one of the pilot areas in REXUS. The carbon footprint of the four most representative crops in the area; olive, orange, wheat and maize, was calculated. The results showed that stone-fruits and citrus fruits such as olives and oranges have a lower carbon footprint than herbaceous crops such as wheat and maize. This is not only due to lower fertiliser and machinery use, but also their land practices cause carbon sequestration.

Q. Who is information useful to and how can it lead to better decisions?

A. Policy makers, natural resource managers and farmers can use this information for better decision making. For example, knowning that carbon footprint of the main crops in the area is mainly contributed to by the production and transport of the fertilizers used, as well as the machinery employed, can make the the more efficient use of fertilizers a priority. Also, knowing that different land use and crop management techniques reduce the carbon footprint can encourage farmers to implement better available techniques. But even setting environmental impacts aside, knowing the impacts of machinery use in crop production can help farmers prepare for potential price increases in fuels such as petroleum products.

Q. Can this work help us better assess and prepare for ‘external shocks’ like last year’s hike in energy prices?

A. On the one hand, this work helps us understand how dependent we are on non renewable resources and fossil fuels in the use of machinery in crop production. On the other hand, it also allows us to understand the different carbon footprints of the energy use mix in the agricultural sector of each pilot area, as the methodology was not only applied to crops but also to energy systems. This will make it easier to meet emissions reductions targets, while additionally, it will help prepare for energy spikes and thus ensure a stable energy supply, including through enabling a transition to clean energy sources.

Q. How to do you think this data can be integrated into the broader WEFE Nexus sustainability vision developed by REXUS stakeholders?

A. Analysing the carbon footprint sheds important light into overall Water-Energy-Food-Ecosystems Nexus dynamics. For example, water is necessary to produce food and energy in hydroelectric systems. Energy is necessary to irrigate crops and use machinery. Thus, a change in one of them can affect the other two. Our work analyses and quantifies the key role that energy plays role in all stages of the agricultural cycle, from soil preparation and irrigation to the harvest and fertiliser production. The broader vision developed in REXUS can integrate the findings of our study in different ways. For instance, different scenarios can be applied to our model to understand how the carbon footprint would change. Right now we are in the phase of implementing the following scenarios:

- What would happen if the energy mix shifted towards more renewable energy sources?

- What would happen if the water use shifted in the cultivation of crops?

- What would happen if the hydropower generation potential changed in the future?

These questions all would provide insights into the models that have been created which also predict the effects of different decisions and scenarios, therefore supporting and complementing their findings.

Q. Has this data been presented to stakeholders and what were their reactions and feedback so far?

A. This data was presented to stakeholders in a workshop in Albacete, Spain. It was received with interest, especially the findings on the dependency on fossil fuels through machinery use, as farmers have been negatively impacted by the spike in energy prices in the past year. Their feedback helped us understand the most frequent issues stakeholders face and the best way to communicate this data.

The 1st REXUS Focus Group meeting with farmers in Albacete, Spain.

Q. REXUS tools for water accounting and footprint were recently integrated into the Júcar River basin management plan, marking an important success in moving from ‘Nexus thinking to Nexus doing’. How can local and national policymakers similarly take into account the data on energy and carbon fooprint?

A. Policy makers can use the data to align agricultural and energy policies, which could involve promoting smart use of fertilisers, energy-efficient irrigation systems, encouraging renewable energy use in agriculture, or supporting less intensive farming practices. Also, it can assist in the implementation of economic incentives, such as subsidies or tax breaks, to encourage farmers to adopt sustainable practices and technologies that reduce carbon and energy footprints.

They can also involve local communities, farmers, and relevant stakeholders in the decision-making process by sharing the data in a transparent manner. By fostering this collaboration, they can ensure that policies reflect the needs and realities of the local context.

Q. What are the challenges of developing and applying this approach?

A. The main challenge in implementing our methodology is data availability. Therefore, estimations and secondary data sources are normally required, and a validation method is used to confirm the results. The lack of real data affects the results, but the main takeaways regarding different scenarios are valuable to understand the high-level impacts of the Water-Energy-Food-Climate Nexus and their carbon footprints.

[1] PCAF, «Global GHG Accounting and Reporting Standard for the Financial Industry,» 2020.

[2] EPA, «Understanding Global Warming Potentials,» United States Environmental Protection Agency, 05 05 2022