For the WEFE Nexus approach to become a truly integrated approach to natural resources management, ecosystem services need to be explicitly valued and incorporated in the analysis, argues Mauro Masiero, Assistant Professor of Forest Policy and Economics at the University of Padova (UNIPD). He explains how the UNIPD team approached the problem and proposed a methodology in REXUS deliverable 3.10, Report on Socioeconomic indicators for Nexus analysis and management, which can assist policymakers make a correct assessment of the costs and benefits of different policies and can also contribute to greater uptake of Nature-based Solutions.

Interviewed by GWP-Med, REXUS Communication & Dissemination leader.

All components of the Nexus are linked together through often ‘invisible’ ecosystem services, which do not have an explicit economic value and are therefore excluded from decision-making processes, argues Mauro Masiero., Assistant Professor of Forest Policy and Economics at the University of Padova.

- Is there a gap in current Nexus analysis with respect to ecosystem services? In the introduction to the REXUS project analysis on Socioeconomic Indicators (REXUS D3.10), you note that “so far Nexus assessments have been mainly focused on the water allocation to different sectors and users, while much less attention has been paid to a broader spectrum of ecosystem services associated to resource management and possible synergies and trade‐offs among them.”

The umbrella term “ecosystem services” encompasses the broad range of benefits ecosystems provide to humankind in the form of security, goods and materials, health and wellbeing. Together with biodiversity, ecosystems constitute the natural capital that is essential to human health and wellbeing.

The Nexus approach is, by definition, a holistic and integrated approach aiming to optimally manage multiple components – namely water, energy, food and ecosystems (WEFE) – to maximize socioeconomic and environmental outcomes. While each of these components is important and deserves specific attention, ecosystems should not just be seen as a separate ‘sector’, but rather as the common ground underpinning the whole spectrum of Nexus interactions.

- What does this mean for Nexus-based policymaking?

Given the complexity of human-ecosystem relationships, and interactions between ecosystem services themselves, policymaking and management choices should not address single Nexus components one-dimensionally, as this may result in unbalanced solutions favoring some Nexus components and, ultimately, some stakeholder groups over others.

For example, when considering an energy policy, we should not only consider its impacts on water, food and ecosystems. A further necessary question is: how does this policy affect ‘invisible’ ecosystem services that may impact all sectors? Central to making an informed decision here is also managing ‘trade-offs’ and ‘synergies’. We refer to ‘trade-offs’ when an increase in one ecosystem service results in a decrease in another ecosystem service, and to ‘synergies’ when two (or more) interacting ecosystem services either increase or decrease simultaneously. While trade-offs and synergies emerge from the biophysical properties of ecosystems and the associated constraints, they are also linked to socio-economic dimensions, as preferences for ecosystem services differ among stakeholders.

The WEFE Nexus analysis of a potential shift in energy policy should go beyond the analysis of water allocations to different sectors and incorporate the explicit and implicit effects on the full range of ecosystem services.

Let’s also take the example of a change in irrigation system. To address the increasing risk of prolonged droughts deriving from changing climate conditions we might consider improving water use efficiency in agriculture by switching from flow irrigation (i.e., through channels) to drip irrigation. While this would likely result in significant water savings, we should also account for possible losses, including those that may not be immediately or visibly accountable. By replacing flow irrigation, indeed, we might lose in terms of water table recharge potential deriving from the intrinsic inefficiency of the flow system, as well as the biodiversity associated with the presence of wetlands or landscape aesthetics and associated cultural values.

A switch from flow to drip irrigation may significantly increase water efficiency, but there may also be an ‘invisible’ loss, in terms of the lost water table recharge potential and biodiversity support.

- Would integrating ecosystem services into the Nexus approach make it too complicated, perhaps unworkable?

Integrating ecosystem services into Nexus analysis only makes explicit what is already implicit within the Nexus concept: water, food and energy are, in one form or another, ecosystem services and therefore directly or indirectly linked to the ecosystems providing them.

The heart of the matter is that some ecosystem services have an explicit economic value – and sometimes even a financial one, i.e., a market price -, while others do not, especially ‘regulating’ or ‘cultural’ ecosystem services. This renders them ‘invisible’ to society and policymakers, which can result in the overexploitation of resource stocks generating those services, and in poorly informed decisions in the design of policies, projects or investments, or choices among land-use options.

- So, is there a practical way to incorporate this dimension in decision-making?

A first step is to value ecosystem services in a way that is understandable to all. Concepts and metrics like ‘cubic meters of runoff’, ‘tons-equivalent of organic carbon’ or ‘hemeroby’ are key for assessing ecosystem services but only understood by experts; on the other hand, monetary values, like euros, can provide a widely understood measure of valuation. In fact, proper valuation of ecosystem services may help make the ecosystem service concept and, by extension, also the Nexus concept, less complicated for non-experts and therefore make it a more ‘user-friendly’ tool for policymakers.

Ecotourism in Lake Ohrida, North Macedonia. Assigning a monetary value to ecosystem services, including to cultural and regulating ones, can be a first step to making their value widely understood and enabling policymakers to take them into account when evaluating different development options.

- How are you developing and applying this methodology in the REXUS project?

Within REXUS, we developed a methodology for the socioeconomic assessment of benefits deriving from Nature-based Solutions (NbS) aimed to support the WEFE Nexus. We aimed to provide examples of literature-based indicators and methods for assessing ecosystem services that could be applicable within the REXUS pilots, rather than exhaustively assess all the ecosystem services involved.

To this aim, our approach consisted of two main steps:

- We identified challenges faced by each pilot within REXUS and linked each of them to one or more ecosystem service and/or non-ecosystem service strategies. Non-ecosystem service strategies consist of consumption and management options, policies, or governance of natural resources. So, for example, for a challenge like “Effect of climate change on WEFE resources” identified ecosystem service strategies include the assessment of (among others) water, energy and food provision as well as water flow regulation, while for a challenge like “Management of transboundary water resources” non-ecosystem service strategies include policy development and water governance solutions. All challenges and strategies identified were discussed and validated together with the pilots.

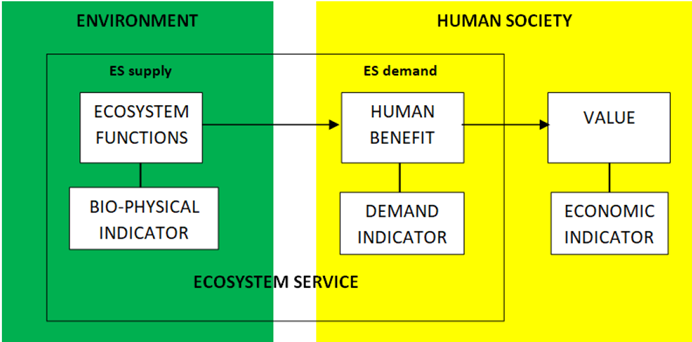

- For all 13 ‘provisioning’, ‘regulating’ and ‘cultural’ ecosystem services identified through the previous step, we tailored socioeconomic indicators. Building on the ecosystem service cascade model originally developed by Haines-Young and Potschin (2010) we defined three dimensions and ad-hoc indicators (see Table and picture below). In total, 39 indicators, i.e., three per ecosystem service, were developed and some of them were tested with reference to the Isonzo-Soča pilot area (Slovenia and North-Eastern Italy).

| Phase/Dimension | Short description | Type of indicators |

| Ecosystem service supply | Assessment of potential ecosystem services delivered by a given environment | Bio-physical indicators for the potential ecosystem service supply |

| Ecosystem service demand | Assessment of potential benefits enjoyed by human society | Demand indicators for the potential benefits |

| Ecosystem service economic value | Assessment (valuation) of ecosystem services in monetary terms | Economic indicators for the monetary value of the service |

- What are the challenges of developing and applying this approach?

The main bottleneck in implementing our approach to assess ecosystem services is represented by data availability. The methodology we proposed, indeed, is subject to some ‘GIGO’ (‘garbage-in, garbage-out’) effect: missing or inaccurate data used as inputs for computing indicators may result in inaccurate assessment of ecosystem services, and this was indeed an issue in our test case, in particular for the Slovenian part of the basin.

It is important to stress that we preferred to develop a user-friendly approach with simple indicators to favor its adoption, extension and up-scaling by pilots, including by non-experts. Therefore, we deliberately avoided using more complex econometric approaches such as demand curve ones, or indirect methods based on revealed preferences (e.g., hedonic pricing and travel cost method) or indirect methods based on stated preferences (e.g., choice modeling and contingent valuation).

- Nature-based solutions are much valued and promoted as a concept of a more sustainable solution providing co-benefits. However, as with the Nexus overall, they are much less applied in practice. How is your work helping address this?

While the NbS concept is increasingly integrated within policies and research activities, there are still barriers to NbS implementation and upscaling. Among these, there are financing constraints and difficulties in creating feasible governance models to design and implement efficient projects that match the participation of all the relevant stakeholders, allowing responsibility sharing and collaboration.

A constructed wetland for wastewater treatment in Kramovik, Kosovo. A full assessment of ecosystem services can reveal the full benefit of Nature-based Solutions and help select the right one depending on each case.

Another key barrier is represented by the lack of assessment of the whole range of ecosystem services that NbS can provide, including co-benefits and trade-offs, as well as costs associated to NbS implementation. This would be very beneficial to the selection of proper NbS, as well as between NbS and alternative solutions, including grey infrastructures. Our work can help fill in this gap by making explicit the implicit benefits associated with NbS.

In fact, in our report we also investigated the relation between ecosystem services and NbS based on existing literature, to provide a preliminary guidance for the selection of NbS by pilots vis-à-vis the challenges they face and the ecosystem services they wish/need to value. Despite being just an exploratory and preliminary assessment, this helped set the ground for more in-depth analysis developed within Deliverable 5.2 of REXUS project, which provides a roadmap to navigate among NbS for addressing Nexus challenges.

Download Deliverable 3.10 – Report on Socioeconomic indicators for Nexus analysis and management